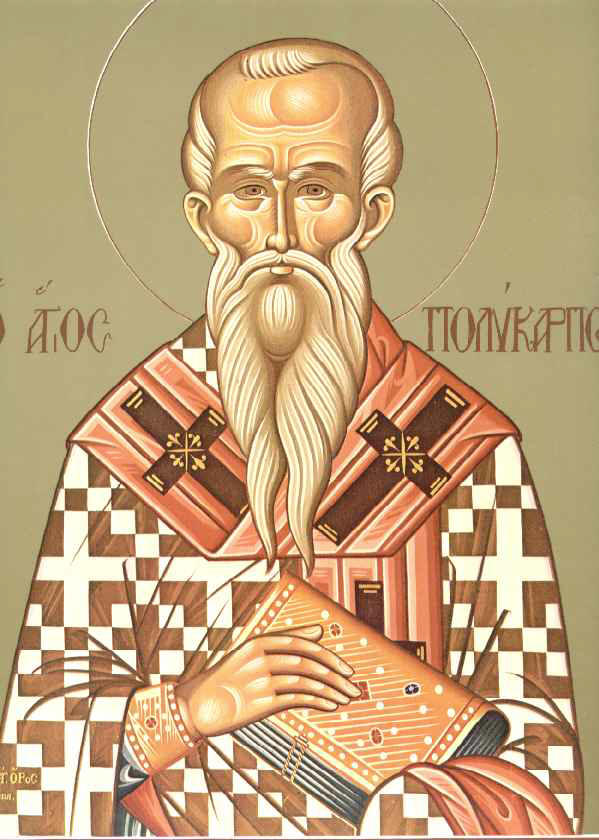

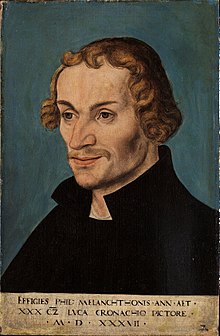

Today the Lutheran Church commemorates Philip Melanchthon, Luther’s colleague in Wittenberg. I debated whether or not I should even add that last part, “Luther’s colleague in Wittenberg.” Melanchthon was more than that. And yet, fair or not, this is how we know him. To be honest, too, I think that appendage, “Luther’s colleague,” is not a diminishment of his work or genius. Rather, that was a very important choice he made, and that in very dangerous times. Philip chose to work with Europe’s greatest theological outlaw and stuck with him, through the darkest of times, and often when Luther made it rather difficult personally—great as he was, the great reformer was not the easiest colleague or friend.

Philip Melanchthon has been called “praeceptor Germaniae,” the teacher of Germany. It’s a title he earned. He shaped higher education in Germany like few others in its history. He shaped the curriculum in Wittenberg, which shaped generations of pastors, lawyers, teachers, and a host of other professions. Melanchthon, beyond a doubt, was a brilliant and influential man.

My students seldom get this reference anymore, but Melanchthon was a Doogie Howser of sorts. He progressed quickly through his education. He graduated young with about every degree he ever received. He was a prodigy, and sometimes suffered for that, being denied admission to at least one program because there was a fear he might become too arrogant progressing so quickly so young. He earned all the letters after his name, though. His mind was a gift from God and he was gifted with a work ethic to match it.

Frail in build, Melanchthon had powerful ideas. Unlike Luther, though, he did not have a powerful personality. He was an intellectual, and a public intellectual, but he didn’t have the demeanor of a prophet. He was thoughtful to the point of being tentative. And that is fine. And the church needs such men. It wasn’t his fault he was cast in Luther’s role after Luther’s death. It was thrust upon him, perhaps unfairly. He was who he was, and his demeanor served him well in many ways, even if it wasn’t suited for the prophet’s task and for the challenges piled upon him with Luther’s death and the great Interim Crisis (which is a post for another day and the main focus of my books An Uncompromising Gospel and The Devil behind the Surplice).

Melanchthon’s great-uncle was the renowned scholar Johannes Reuchlin, famed for his work with Hebrew and the trouble that got him into. Reuchlin had overseen Melanchthon’s education. And yet the relationship between the two soured because of Melanchthon’s loyalty to his colleague and friend, Martin Luther. Melanchthon refused to take a position elsewhere when things heated up with Luther’s Reformation, as we refer to it now. He was committed to Wittenberg, and more importantly to the Scriptures and justification by grace through faith for the sake of Christ. In fact, Melanchthon supplied much of the language we use now to express that as clearly as possible.

Today we give thanks for the life and thought and confession of Philip Melanchthon. Those of you who know me and my work know that I work especially with the life and thought of Matthias Flacius Illyricus, a student of Melanchthon’s who later became an opponent. I’ll admit to sharing much in common with both the demeanor and the theological emphases of Matthias Flacius. I will also say, though, that through my work with Flacius I have grown in my appreciation for Melanchthon. This was a man who sacrificed for the Lutheran Reformation. This was a man who put his time and health into the study of God’s Word and into the instruction of its preachers. This was a man, too, who bore a heavy cross especially after Luther’s death. Like all of us, he struggled under it. And yet, I pray, like all of us, he kept his eyes on Christ, even as he wavered. We do well, then, to give thanks for him and to learn from him, especially from works like the Augsburg Confession and its Apology, his 1521 Loci Communes, and other theological treasures. This was a man who knew Christ and knew Paul, and in that faith, rooted in Christ and shaped by Paul’s beautiful teaching about Christ, he departed, weary from years of theological struggle. God grant us all the same!

If you want a short and accessible little book on Philip Melanchthon, I highly recommend Meeting Melanchthon by my friend and Melanchthon scholar, Scott Keith

Wade Johnston

For more content like this, check out the podcast, blog posts, and devotions at www.LetTheBirdFly.com.

You can listen to our latest episode here. You can find our latest installment in the Wingin’ It series on Luther here.

For more writing by Wade, you can find his books here and more blog posts here. You can visit his faculty page, which lists other writings and projects here.